Name: Joe Levi

Practice Area: Civic

Years at OZ: many, many, many (started in 1978)

What sparked your interest in architecture?

As a boy, I was drawn to building. I grew up near many streams and would play in the water, building dams and new channels with my friends. After being yelled at for tracking mud into the house all the time, I switched to constructing indoors. My favorite toys were my Lincoln Logs, brick set (a precursor to Legos), and my favorite a set of plastic beams, columns and panels based on international styles of architecture. When I saw the New York World’s Fair in 1964 and the Montreal Expo in 1967, I was totally smitten.

As a young man, when I was considering what profession to pursue, we were in the height of the Vietnam War. Times were very different back then, so a lot of young men like me had to choose between enrolling in school or potentially being drafted into combat. Architecture intrigued me and seemed like better, more creative fit than studying law or medicine.

Tell us about your career journey and what led you to specializing in your practice area.

I came to public work by serendipity. I started working at the first iteration of OZ Denver, which was called McOG, in 1978. After graduating from the University of Cincinnati, I worked for over a year at a local design-build company. I had helped design a large open-air shopping park located in the Tech Center and went to the AIA office located next to McOG to see what else I could do. McOG happened to have a “Help Wanted” ad in their window, and I set up an interview.

At my interview, I saw a model in the corner of the future Spectrum building and told them I felt confident in my abilities in design and detailing for retail, but didn’t know anything about mid-rise buildings. The interview went well, and my second project at McOG was the Spectrum Building. It was taxing, but fun, and I went on to manage some the largest projects at McOG, quickly becoming a partner.

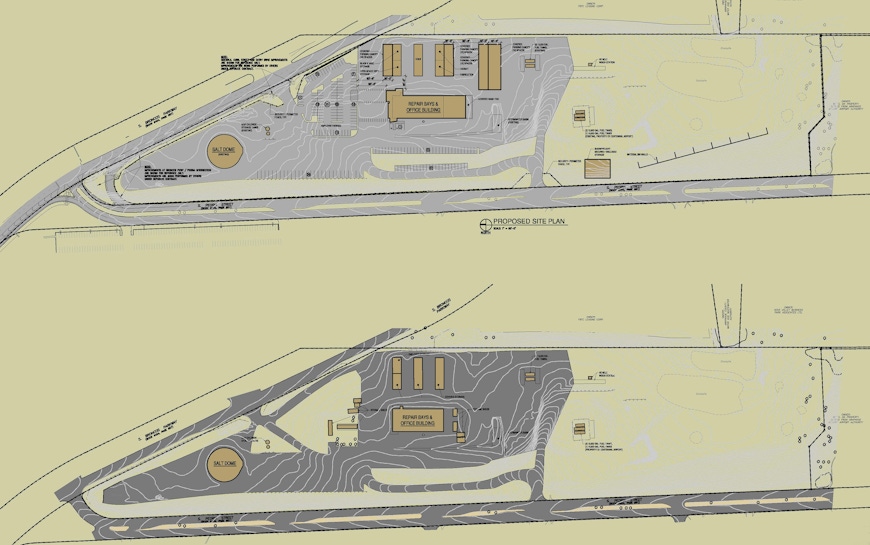

Having worked on spec offices, our work dried up around the recession of the early ‘80s. An opportunity then came up to do a master plan for Arapahoe County, so I took a chance to put together a proposal with the help of Eliot Goss, a firm founder, and Dan Paulin, a friend of a friend. We won, and I never looked back. Since that first project, I’ve been fortunate to work for most Colorado Front Range communities on more than 100 civic projects, small and large, with a concentration here in Denver.

What’s something people might not know about your practice area?

Civic architecture is highly competitive at all levels. There could be over 50 firms vying for projects with national competition — Norman Foster & Steven Holl and The Denver Justice Center, Snohetta and Boettcher Concert Hall, Bruce Kuwabara and The Web Building, Gio Ponti’s old firm and the Denver Art Museum — and that’s how it continues to be in civic work.

How would you describe your design approach?

Listen, listen, listen. Success depends on understanding what’s important to each individual stakeholder and the surrounding community, and to do that, you must listen. Architects are sincere, talented and hardworking, but haven’t always developed the skills to listen and guide a project beyond the desired outcome without losing site of the client’s goals. My design approach leans heavily on this philosophy, and I work hard to teach others in my practice area the same strategy.

What is the most difficult part of your job? Your favorite part?

The most difficult part of my job has been advocating for our civic practice. On the reverse, my favorite part has been helping the firm see that pursuing civic work is the right thing to do. Our civic practice benefits the business and is good for the community.

What are some of the most interesting projects you’ve worked on recently or are currently working on?

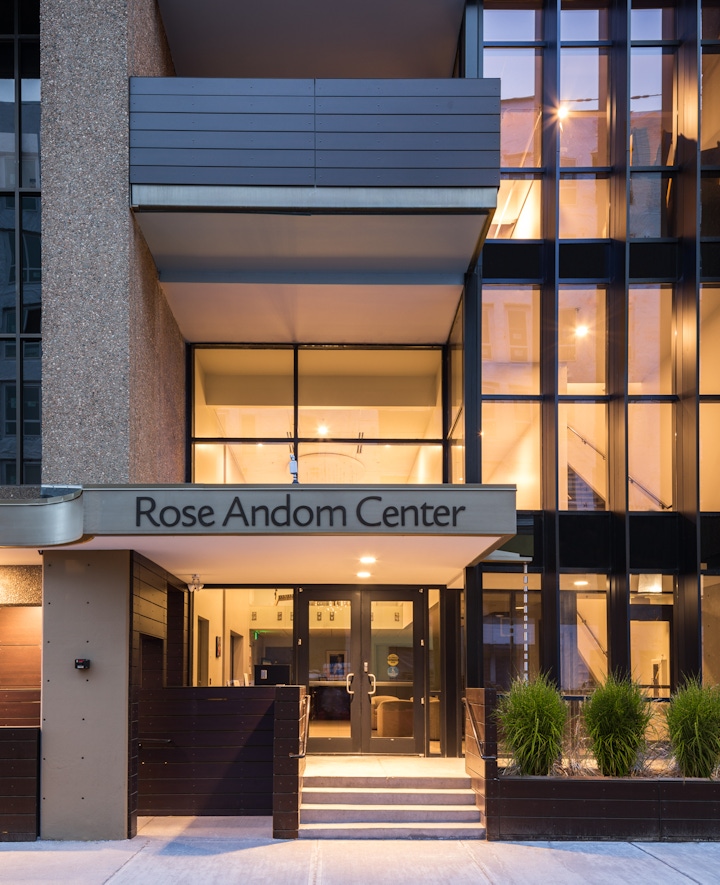

My favorite project, to this day, is the Rose Andom Center. The center is a place for victims of domestic violence to find safety, support and services to rebuild their lives. Working with incredibly dedicated clients pursuing this dream for over 10 years, alongside Robert Willsie, who made a Class D building into a sanctuary, was incredibly fulfilling. I marvel at what architecture can do to uplift and provide hope for our communities.

What are three personal things about you that people might be interested to learn?

As you forecast, what does the future hold for your practice area (e.g. evolution of the PA, new concepts, trends in the industry, etc.)?

Our clients provide services to the public; most are not very glamorous. Architecture provides a new environment and a way for the users to engage with their space, bringing some creativity and excitement to their routines. As changes are few and far between, trends need to be considered for their long-term effects. The immediate need is to fill civil jobs. With virtual offices helping to alleviate the lack of manpower, we are turning our efforts to wellbeing and configuring our spaces to allow varied environments to increase productivity. The future will be challenging and exciting. While keeping up with the rapid advancement of technology will continue to be challenging, I have faith that the profession will continue its long arc.