Name: Rick Petersen

Practice Area: Cultural, Urban Living, Workplace

Years at OZ: 32

What sparked your interest in architecture?

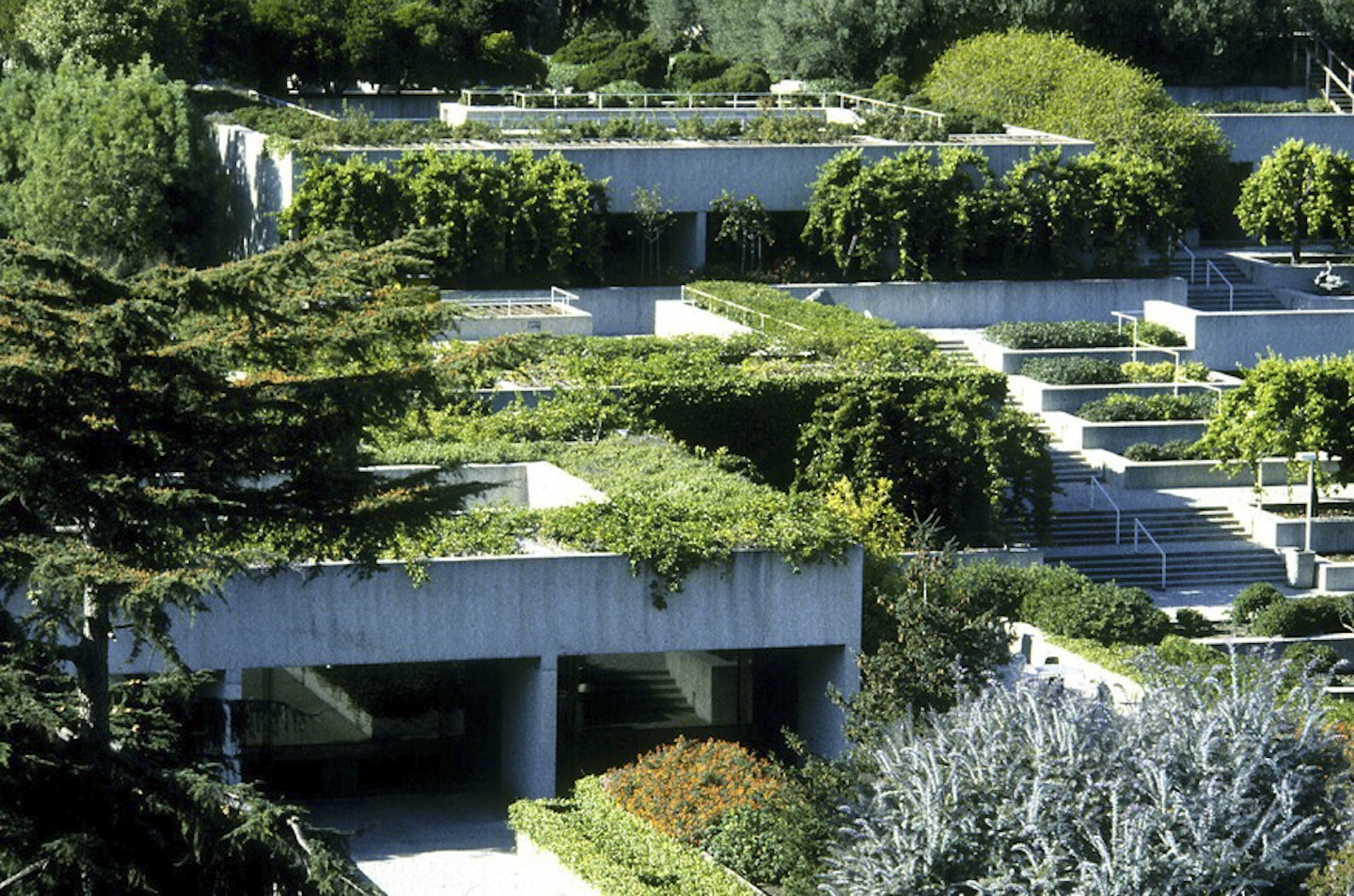

Growing up in Northern California, my father, an agronomist, worked with leading designers like Lawrence Halprin and architects like Kevin Roche to integrate landscape with architecture. I was inspired not only by the projects, but also the process of multi-disciplinary design.

Tell us about your career journey and what led you to specializing in your practice area.

I was incredibly fortunate that my first employer insisted that I start not with just bathroom or stair details, but rather an entire project: A trash can enclosure and carport.

This sounded easy enough, but there I was navigating between the owners (who couldn’t agree on the size), the zoning board, the structural engineer and contractor. While not knowing it, the project prepared me for a career of collaboration.

This served me well upon arriving in hyper-collaborative Denver, where I started work at OZ in 1991 after graduate school.

Almost immediately I found myself in the “front seat” of the new practice of sustainability and its emphasis on integrated design. Early work included a collaboration between with the National Renewable Energy Labs (NREL) and the National Park Service on the design of energy-efficient housing in the Grand Canyon.

This lead to my first major project, the Prairie Learning Center for the US Fish and Wildlife Service in Iowa, incorporating new strategies like geo-exchange, triple glazing and daylighting in exhibit spaces — this was all before LEED certification became mainstream.

Soon thereafter I lead our team to develop National Sustainable Design Guidelines for the USDA Forest Service, and several branches of the National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS), an organization with the mantra, “Leave no Trace,” foreshadowing today’s Net Zero design.

Beginning in the late ‘90s, I began to lead local educational projects, including the Longmont Museum, Fort Collins Museum of Discovery and the Children’s Museum of Denver, all of which formed the basis for OZ Architecture’s Cultural Practice Area.

While leading this practice area, I’m in fact a generalist who’s been fortunate to design for a crazy breadth of building types, from workforce housing and corporate headquarters, to historic adaptive re-use projects and a variety of essential community fixtures, including a town hall, a movie theater and a church.

What’s something people might not know about your practice area?

Our Cultural Practice Area’s largest project, McMurdo Station in Antarctica was awarded to us not for our experience, but for our lack of it. In this (rare) case, our client wanted “Fresh Eyes” to reimagine the station. This echoes our firm’s belief that A Beginner’s Mind fosters innovation.

How would you describe your design approach?

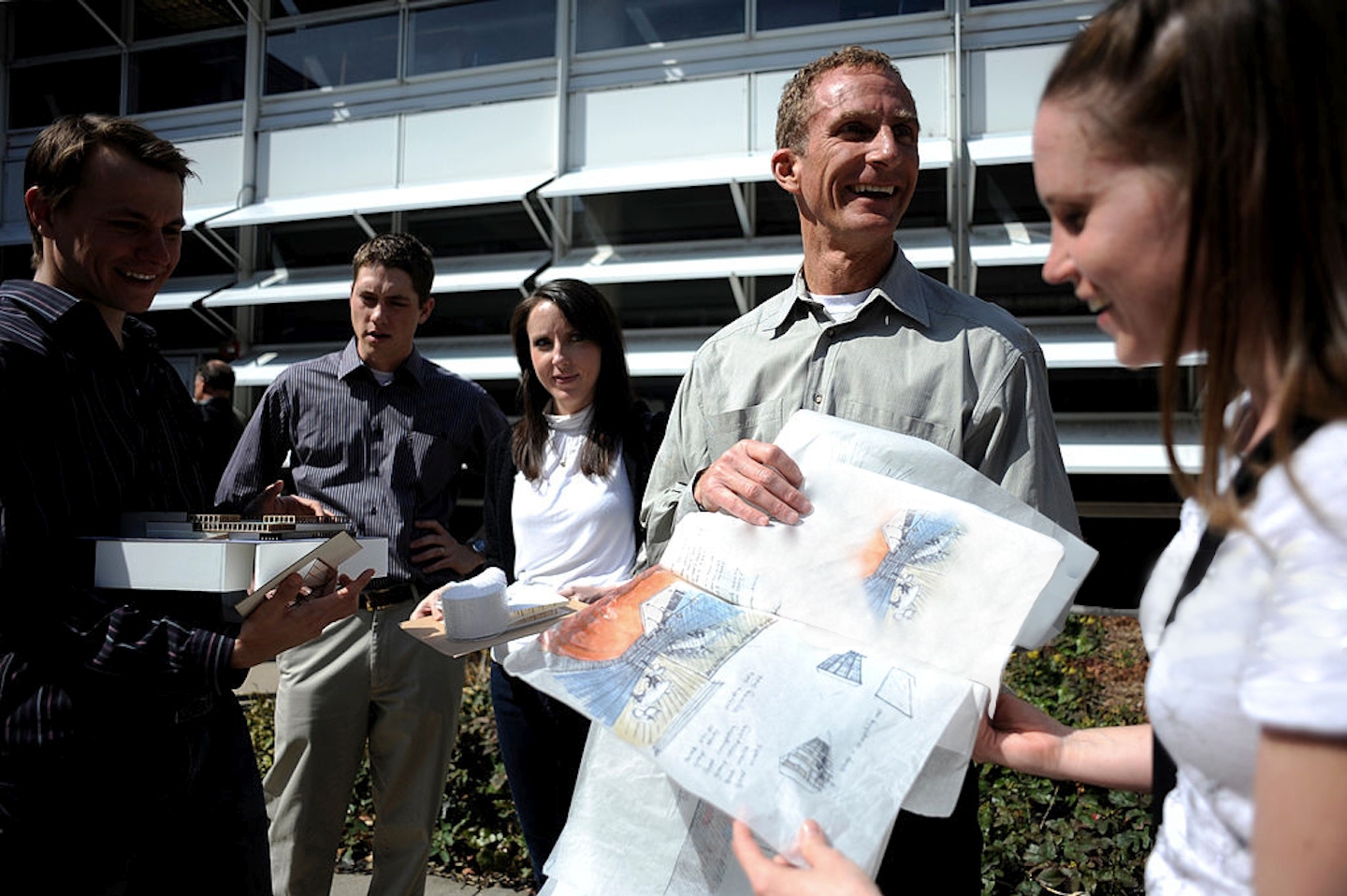

First and foremost, I work hard to get the right talent around the table. It’s one of most satisfying aspects of my work.

Throughout the process, I support an environment of empowerment and accountability, where all team members have both the opportunity and the responsibility to contribute to realizing the design. I don’t care where a good idea comes from. That said, it’s my job to be the design steward, where I continually inspire the team and client to maintain the design intent.

Through this all, our goal is to synthesize all the project requirements to not just meet the client’s goals, but to unearth a special aspect of the project that wasn’t even a part of the program—like the interweaving of park space and housing units at our Denver Housing Authority’s Sun Valley Community.

What is the most difficult part of your job?

Filling out expense reports.

Your favorite part?

True to my generalist style, I have not one but three answers:

What are some of the most interesting projects you’ve worked on recently or are currently working on?

I’m especially excited and proud of our Denver Housing Authority Sun Valley Community project. Being the first block to be redeveloped in this precinct, the project is a catalyst to inspire a new neighborhood focused on two of today’s most critical issues: equity and wellness.

Another is the Butterfly Pavilion, a treasured Front Range institution that is relocating and expanding as an international center for the study of invertebrates. Accounting for 97% of the world’s species, these butterflies and pollinators are criterial to our planet’s health.

What are three personal things about you that people might be interested to learn?

1) Two experiences shaped my—so I’m told—“seize-the-day optimism.” First, our daughter Anna was diagnosed with Leukemia at age six, and is now a healthy supervising oncology nurse and expecting her first child.

Second, in 2009 while training for the Mount Evans bike race, a drunk driver drove head-on into me, leaving me in a wheelchair for four months, granting me a keen appreciation for accessibility codes. With support from my family and our team at OZ, I recovered and returned to racing, finishing 1st four years later. My daughter and I are lucky to be alive.

2) I love growing things. In addition to heirloom tomatoes, indoor orange trees and the microbes of sourdough bread, I’m most fulfilled by having helped grow our two amazing daughters Anna and Maggie. Now my focus is the remarkable young architects I get to work with every day at OZ, and those whom I teach as Professor in Practice at UCD’s College of Architecture and Planning.

3) I’ve been to Antarctica several times and am one of the few to have visited each of the United States stations, which serve the purpose of supporting the National Science Foundation. Flying over the continent’s vast ice cap, which contains 70% of the world’s fresh water, left me committed more than ever to help in the understanding of climate change.

As you forecast, what does the future hold for your practice area?

Our Cultural Practice clientele are mission-driven. That means that there’s tremendous opportunity to design sustainable, resource-efficient facilities that reduce operating costs, leaving more hard-earned dollars for their programs.

And as for the challenging fundraising efforts, I’m seeing the value more than ever in the role we play to convey a compelling vision, then advocate for it on behalf of our clients. This is an incredibly rewarding part of my job.